|

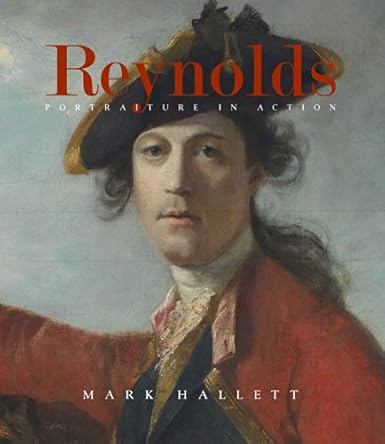

| Picture: Amazon |

Sir Joshua Reynolds has been well-served recently, with an excellent catalogue raisonné by David Mannings and now this magnificent monograph by Mark Hallett, focused on the historical and artistic context of Reynolds' art. Each chapter takes a different slice of Reynolds' oeuvre, such as his Royal portraits, his series of portraits of 'great men' known as the Streatham Worthies, and his full-length portraits of women whose presentation at the Royal Academy he reconstructs. Generous comparative illustrations show Reynolds' sources in artists like Van Dyck and earlier English painters, some of which are unexpected. The book is interesting throughout. Inevitably it is often speculative, particularly when assessing motives and reception, but Hallett's command of the evidence and sensitivity to context is admirable.

|

| Picture: WikiArt |

A particularly interesting chapter on the Marlborough family portrait (pictured above) concludes on a critical note that, whilst well-put and strongly argued, is one point on which I disagree with Hallett. He writes:

"as a coda to this investigation of intimate touch within Reynolds's portrait, I would like to draw attention to what seems to me an unusually awkward, malfunctioning passage of his painting. This is the gesture made by the duchess's left forearm as she, like her youngest son, points at her husband's cameo. To my eyes, when I see this forearm swinging listlessly from the duchess's elbow like the minute hand of a broken timepiece, I want to make it do something that seems so much more in keeping with the rest of her body language - I want it to follow her gaze and to reach out, perhaps to rest on her second son or daughter's shoulder, and in so doing make up a chain of gestures and touches that one can imagine continuing along either of these children's own outstretched left arms, and ending in the fingers that tenderly cling to Lady Caroline's right shoulder. The ghost of such a pictorial sequence - one that would once again directly link a mother and her growing children together - haunts this image. Instead, of course, the duchess dutifully follows her husband's lead, just as Reynolds, in painting this limp gesture, seems himself to have done. It is, to conclude, his one false touch and something - however seemingly minor - that betrays the difficulties and tensions involved in keeping so many agendas and narratives in play, all at once, within a single image." (pp. 338-339).

But the duchess is the linchpin tying together the two parts of the composition, on the one side her cerebral husband and his heir; on the other side the more animated group of children. If her arm rested on her second son's shoulder it would establish a strong second diagonal in the right hand group, running along two pairs of arms. On her daughter's shoulder, it would establish an arc joining the children together. The effect of either action would be to separate the two parts of the composition, and to establish a too tightly knit group on the right. Reynolds could perhaps have tempered that effect by having the duchess gaze towards her husband, but that would look oddly disengaged from the children with whom she would then otherwise be so intricately linked.

Hallett reads her 'limp' gesture as dutifully following her husband's lead, but here too it can be read differently. As Hallett notes, she gestures towards an ancient cameo held by her husband. Therefore she is implicitly referencing an historical and cultural world beyond the family, perhaps with an eye to posterity, but perhaps also hinting at her own cultural interests. I see the gesture as touching rather than limp, and I think Reynolds was conscious of the need to soften the duchess's impact in the picture given her dominant central position.

I appreciated this picture a good deal more after reading Hallett's chapter. But it seems to me still to suffer from a kind of ersatz heroism that turns me off Reynolds. There's something false and sometimes histrionic about Reynolds' borrowings from art history. Those great solomonic columns are redolent of Raphael and the high renaissance, but they seem dreadfully out of place in eighteenth century England. I freely admit that the fault is probably on my part rather than Reynolds's. But his borrowed grandiloquence has always struck me as phony, whereas I can happily believe in Gainsborough's equally false arcadian idylls, or Lawrence's grand martial portraits of army officers who were likely fat and inept.

I dwell on this point because it interests me, not because it's a significant critique of Hallett. The book is superb - certainly one of my books of the year.

Are you paying over $5 / pack of cigs? I buy high quality cigarettes from Duty Free Depot and I save over 50% from cigs.

ReplyDelete