Yesterday Sotheby's announced plans to return capital to shareholders, responding to 'much welcomed feedback and input from investors' (like Dan Loeb, who called for the CEO to be sacked). They are taking lots of predictable steps to cut costs and return capital to investors. One of the more curious aspects is the separation of Sotheby's Financial Services ('SFS') from the auction business.

SFS is essentially a pawnbroker, lending money against art. Its competitive advantage is that it knows the art market. Its competitors in the finance industry cannot value art as collateral, and cannot easily sell it if they have to repossess. Sotheby's will often know the identity of the underbidder, and know the other collectors who will be interested. The hefty auction transaction costs are paid to Sotheby's itself. The business couldn't work without that relationship.

They now seek 15% return on equity in their auction business, and 20% in their financial services business, which lends money against art. Return on equity is a measure of how much profit a business generates from the investor's funds. It can be increased by borrowing more money (leverage). For example, if you buy a house for £1m cash and sell it for £1.1m, your return on equity is 10%. If you did the same trade with a £100k deposit and 90% mortgage, your return on equity is 500%, minus and interest paid. In the boom years, banks increased return on equity by borrowing more money. That boosted returns in the good years, but increased risk when things went wrong. The attraction of lending to Sotheby's is that they typically have a lot of cash on-hand, because they are paid by buyers before transferring money to sellers - so their cashflow cycle should be positive, notwithstanding seasonality. Lending it out via SFS is more attractive than depositing it at the bank.

The higher target return in the financial services business seems driven by increased leverage. It is repaying an inter-company loan, and taking on the whole of the firm's credit facility. I assume that the facility is guaranteed by the parent company (or directly to the parent company), as the finance business is too small, too volatile and too uncertain to be able to borrow at good rates. And it couldn't succeed without Sotheby's' expertise and relationships. Given SFS's dependency on Sotheby's, separate return on equity targets are really internal accounting adjustments.

Lending money is the easiest business; there are always willing customers. The skill is in getting it repaid. Sotheby's seems remarkable relaxed about repayment, with high levels of loans 30 days and 90 days past due, and a volatile split between 30 days and 90 days past due. That reflects the specialist nature of the business, with relatively large loans against good collateral. I suspect they boost returns by charging additional fees on over-due loans, without worrying too much about when they are repaid because they are confident in the collateral. But lending is inherently extremely risky, and has the potential to swing into huge loss when things go badly. I hope for a lot more disclosure on the finance business in their accounts, so that investors can assess the risks independently.

If you can get past the inelegant corporate-speak and the 'going fowards' (don't they read Lucy Kellaway?), the strategy review seems broadly sensible, with better cost discipline and a more efficient capital structure. I think Sotheby's is wise to resist the more extreme demands of the activist investors, who want to squeeze cash out of the business to get a quick return. Auctioneering is a cyclical business; it's prudent to retain capital for tougher times. But growth plans for SFS introduce significant risk, and performance is hard to assess with the limited information provided in the accounts. The differential return on equity targets involve a degree of smoke and mirrors, and increasing leverage means increased risk.

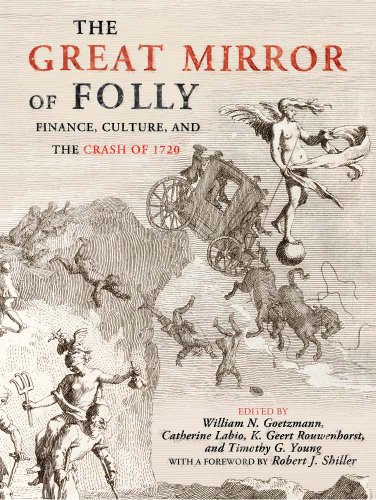

![A broadside the South Sea Bubble and other investment schemes of 1720; with an engraving showing on the L a man seated in the air on clouds, distributing papers with his L hand, behind him two other men, one using bellows and blowing away a cat attached to four balloons, in the R foreground a chest filled with papers attacked by mice; with engraved titles, inscriptions, and verses in three columns. (n.p.: [1720])](http://www.britishmuseum.org/collectionimages/AN00320/AN00320480_001_l.jpg?width=304)