|

| Picture: Amazon |

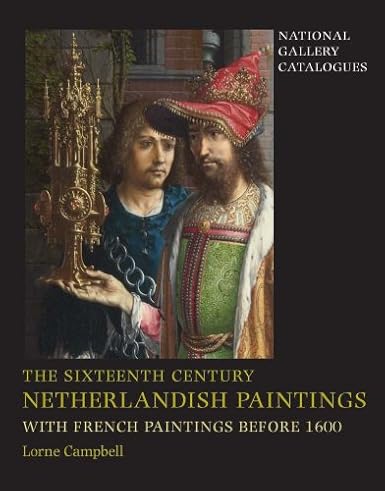

This is close to the Platonic ideal of a museum catalogue. It's an outstanding work of scholarship by one of the most eminent experts in the field. And it is beautifully produced with generous illustrations of excellent quality, including details and photomicrographs. The introductory essays are brief; this isn't the place to look for a history of sixteenth century Netherlandish painting. But the essays on each artist are much more substantial than the usual potted notes one finds in museum catalogues, and together constitute a really valuable guide to the petits maîtres of the time.

This catalogue covers one of the weaker areas of the National Gallery's encyclopaedic collection of European painting. Major works by Bosch and Bruegel were fortunately acquired in the early twentieth century (though still no Bruegel landscape), and there's a strong collection of Mabuse including the exceptional Adoration of the Kings, but there are many gaps (nothing by Patinir or Frans Floris, for example). Perhaps it is out of place in a scholarly catalogue, but I'd love to know Campbell's desiderata - which ones got away?

There are a number of duds in this part of the National Gallery's collection, mostly acquired as part of larger bequests, but even these are discussed with great care. The lavish catalogue entries seem dissonant for pictures such as the female portrait from Quesnel's workshop (NG 3582), or the ruinous male portrait simply attributed to the French school (NG 3539). But many individual entries are exceptionally masterful, such as the lengthy discussion of Mabuse's Adoration of the Kings, with a superb refutation of Ainsworth's claim that it's a collaboration with Gerard David. Campbell's admirably clear writing makes even the most recondite details compelling. Two Tax Gatherers from the workshop of Marinus van Reymerswale is brilliantly compared to the primary autograph version in the Louvre, establishing the precendence of the Louvre version but also sensitively appreciating the fine qualities of the London version, particularly in the draperies.

These expensive volumes are aimed at a specialist market, but the National Gallery has wisely and generously made a number of entries freely available online, including the great Mabuse. I think that entry should be required reading for first year art history students, as a model of connoisseurship and of academic writing at its best.

Most aspects of this catalogue cannot be praised highly enough, but it has a fatal shortcoming that is common to this series, which is the lamentable reticence when discussing condition, and particularly when discussing the history of the National Gallery's own conservation efforts.

The entry on Bosch's Christ Mocked quotes Helmut Ruhemann as saying that he had "never seen a Bosch in such a good condition, and that it would gain greatly by cleaning" (p. 144). It does not say that Ruhemann , the former NG conservator, has done more harm to Britain's paintings than anyone else who has ever lived. He was an influential self-publicist who aggressively over-cleaned, and taught a generation of restorers to scrub pictures within an inch of their lives, and then repaint any obvious gaps themselves. Campbell doesn't pass comment on the claim that Ruhemann's work on the picture in 1934 was limited to 'removing old varnish' and 'slightly making up' some shadows in Christ's robe. Nor does he comment on the two subsequent restorations in 1954 and 1967, the latter including a new cleaning and re-varnishing apparently required within just three decades of Ruhemann's intervention.

Parts of that Bosch seem very worn, and I would like to know how much of that is down to the National Gallery's own restorers. An obvious way of judging is to show before and after pictures. Files that I've consulted in the National Gallery's own archives include extensive restoration pictures; Ruhemann had no shame, and documented his butchery carefully. But despite the wealth of illustrations in this catalogue, we are never given before and after photographs to show how pictures were changed. Ruhemann's work was controversial at the time, but today is almost universally seen as destructive. But you'd get no sense of that from this book.

Campbell often describes glazes as 'faded'. I haven't found any instance of his saying that they were wrongly removed by inept restorers at the National Gallery, thought it is widely known that this is what happened. I don't mean to deny that glazes can fade, but the more common problem (especially at the NG) is that they are removed by over-cleaning. Comparison of pictures at the Louvre and the National Gallery clearly reveals the effect of the former's more conservative approach to restoration. But Lorne Campbell thinks that it shows only that London's pictures are more faded; he explicitly states that this is the case with Louvre and NG versions of Two Tax Gatherers. Perhaps they are simply more careful about keeping the curtains closed at the Louvre.

There are multiple other examples of reticence about the National Gallery's own mistakes, and overly generous assessment of condition. The Mass of Saint Giles by the Master of St Giles was restored after an 'accident' at the gallery in 1933, but we are not told what happened. The Holy Family from Joos van Cleve's workshop is described as being in 'fairly good condition; Joseph's head is better preserved that the Virgin's or Christ's', which is a circumlocution to avoid saying that the Virgin's face has been seriously abraded (p. 223).

I dwell on these points because if the National Gallery will not confront its institutional history then we cannot trust it to act responsibly today. Ruhemann propounded a clear philosophy of restoration that is now utterly discredited. Does the National Gallery now repudiate that philosophy or not? I do not hold the current staff responsible for historic errors, of course. But prevaricating about those practices raises profound questions about their ability to make judgments about restoration today. This is a truly excellent catalogue, but that should not blind us to the magnitude of sin in its panglossian account of the condition of the NG's pictures.