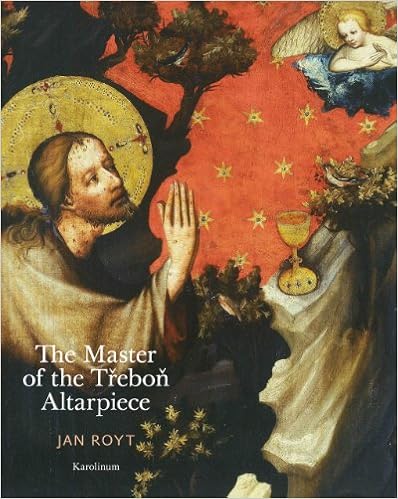

Jan Royt The Master of the Trebon Altarpiece Carolinum Press 2015 £31.50

This is a book and an artist worthy of more attention. The artist's work is almost all in Prague, and the book was published by Charles University and seems not to have been widely reviewed. But the pictures are amazing, as you'll appreciate from the book's high-quality plates. The solidly academic text explains multiple contexts for the Trebon Master and discusses his known works. Its style is a little formal, and I thought it could benefit from the structure of a traditional catalogue raisonné, rather than an analytic monograph. As it is, parts of the text read like catalogue entries pasted together. But the quality of analysis is high, and the book is worth getting for the pictures alone.

Frank McLynn Genghis Khan: The man who conquered the world Bodley Head 2015 £25

This enjoyable popular history narrates the astonishing rise of the Mongols, who went from being central Asian subsistence nomads to conquerors of most of the known world, from China to eastern Europe. McLynn focuses on the great military campaigns which are both the most salient aspect of Genghis Khan's reign, and the best documented. But he ranges widely, discussing administrative practice and religious beliefs, which seem to have been rather new-age ecumenical. He leaves grand speculation on the causes of the Mongol hegemony to the last chapter, which I found least satisfactory and overly hasty in downplaying environmental factors. But although I learned a lot from the book, I was frustrated that the narrative pace trumped historical scruples.

Sources on the Mongols are partial, biased and ancient. Reportage and myth are entwined. McLynn is a popular historian trying to tell a good story, so he doesn't pay enough attention to uncertainty. It struck me when he wrote definitively about the Mongol's skill as warriors, including the ability to time their shot at the exact moment when the horse's feet are all off the ground (p.130). But people didn't even know that horses even raised all their feet off the ground at once until Muybridge's photographs. Makes me wonder about the other claims, including the remarkably precise report of the archer who shot a bow 550 yards in a contest in 1225. He suggests that despotism is against Buddhist creed (p. 143); he should read Brian Daizen Victoria's Zen at War.

McLynn has a peculiar fascination with alcohol. Massive piss-ups are a staple of ancient culture, and hardly confined to the Mongols (though the shift to higher-alcohol wine was a shock to their system). But for McLynn it's an opportunity for wild speculation: "As a student of human nature, [Genghis Khan] knew that a ban or prohibition would be a pointless gesture which would not work, so he tried to moderate the problem by decreeing that none of his subjects should get drunk more than three times a month" (p.158). Remarkable that he was so much smarter than our current rulers, but of course it's an evidence-free assertion. Later McLynn writes that "Severe alcoholism was the major reason for the short lifespans of the great Mongol khans and aristocrats" (p. 363). That's an absurd assumption that tells us more about the author's preoccupation with a fashionable cause of our own times than about the health of thirteenth century warrior elites.

Academic and popular history are needlessly far apart. Often academics are to blame for bad writing and an excessive preoccupation with their peers rather than their sources, and also for a sometimes snooty disdain for history written by non-academic historians. But often the fault is with popular historians who are cavalier with evidence and think that telling a good story is sufficient. This book has many merits, and its daft speculative moments damage its credibility.

Academic and popular history are needlessly far apart. Often academics are to blame for bad writing and an excessive preoccupation with their peers rather than their sources, and also for a sometimes snooty disdain for history written by non-academic historians. But often the fault is with popular historians who are cavalier with evidence and think that telling a good story is sufficient. This book has many merits, and its daft speculative moments damage its credibility.

Rachel Laudan Cuisine and Empire: Cooking in world history University of California Press 2015 £19.95

Satisfying big history packed with delicious morsels, taking us from prehistory to the present day. Love the old warnings against vegetables, and the Soviet caution against drinking too much water. Laudan is a smart cookie who keeps a sense of narrative sweep holding together the details. For much of history innovation was limited to elite food; everyone else was stuck with dull staples. ‘Middling cuisine’ arose late, giving us all better and more varied options. She is cautious of the moralistic critique of diet, rightly celebrating our great success in providing such rich and varied food for all.

Bernd Roeck Florence 1900: The quest for arcadia Yale University Press 2009 £25

The years from about 1890 to 1914 are some of the most fascinating in human history, a time of change that eclipses our own supposedly unprecedented dynamism. It was a time of rapid urbanisation, and cities like Vienna, London, Paris and New York led the charge. This book can be read as a fascinating oblique take on these changes, writing about a city that even in 1900 was becoming a tourist shrine, despite rapid growth. Roeck focuses on expatriate communities, the Germans and English who made Florence their home. It's remarkable to read about the extent of destruction in central Florence at this late date, and of plans for even more thorough-going redevelopment. I enjoyed it less than I expected; its tone is a little dry, and much of the material about expats was familiar to me from other sources. But weaves together a magnificent kaleidoscope; how wonderful it must have been as part of that cultural circle.

Frank E. Zimring The City that became safe: New York's lessons for urban crime and its control Oxford University Press 2013 £13.49

Crime rates have collapsed across the western world. It's one of the most amazing social developments, yet good news stories prompt less discussion than bad. The rapid rise in crime from the 1960s prompted an industry of hand-wringing and competing explanations powered by different biases and ideologies. It's fascinating on many levels, and deserves much more attention; I'm always glad to find smart books addressing the question.

New York's crime statistics led the way up and down, and Zimring's book tries to explain it. I hadn't appreciated just how dramatically crime fell in NYC (99% decline in auto crime, for example). And some of the common explanations, like zero-tolerance, are less important than is commonly believed. Unfortunately the dearth of studies at the time means that data aren't available to test some hypotheses. But just as those in charge were blamed for rising crime rates, so those in charge more recently are credited with bringing about decline, and we accept their explanations too readily. Impressive book, and the lack of definitive answers is a failing of the data not the author.