|

| Picture: Metropolitan Museum of Art |

The most exciting upcoming exhibition this season is

Bartholomeus Spranger: Splendor and Eroticism in Imperial Prague at the Met in New York. Spranger isn't a household name, and he isn't one of the very greatest artists. But this show is much more worthwhile than a routine 'big name' blockbuster because it draws attention to an artist who is too often neglected. Spranger is not well represented in major museums, and he's a bit out of the central narrative of art history (eccentric Bohemian mannerists are denied their week's lecture in most survey courses, more's the pity). The Met has a great record of mounting shows like this, usually accompanied by brilliant catalogues. I'm making a special trip to New York to see it. And as an added treat, there's the Leonard Lauder collection of cubist art and

Grand Design: Pieter Coecke van Aelst and Renaissance Tapestry. This is what exhibitions should be about - fresh light on original and interesting subjects. I can't wait!

Meanwhile in London there's a tedious roster of rather predictable blockbuster exhibitions opening this autumn. Most are obvious shows of artists who have been exhibited exhaustively and exhaustingly, but are well enough known to draw crowds.

The Royal Academy has had some great recent exhibitions like

Chiaroscuro Woodcuts, and the highlight of this season in London is their

Moroni show. There are an awful lot of Moroni portraits at the National Gallery (they even once considered selling some), but I'm looking forward to a rounded presentation of this talented artist. But the RA has also hosted some of the flimsiest recent shows, which don't pretend to be anything more than entertainment. Catalogues have been a travesty - some colour pictures with captions, plus a few brief essays by celebrities. I'm already put-off by the excessive and daft publicity for Moroni, which presents him as a precursor to Caravaggio and Manet. Oh puhleeze.

They've out-done themselves in the promotional material for

Rubens, which re-assures a public unschooled in the classics that "the show would make them not worry about details they did not understand". Curator Van Hout just wants to "cheer the public up". That's the most shamefully dumbed-down publicity I've seen for a major show. Yes, exhibitions are there to be enjoyed. But surely at least part of the point is to challenge and educate too. A more focused

exhibition of Rubens' tapestries at the Getty looks more worthwhile. Manageable size and meaningful focus. And they do good catalogues at the Getty.

Then there's Late Turner (again) and another Constable show at the V&A. The pairing is supposed to allow us to assess their relative merits, which is a rather obvious conceit. Turner is clearly the better painter (although I must confess to preferring Constable). There aren't many great British artists, so they just get exhibited over and over again in predictable ways. Late Turner especially will be mobbed, I'm sure. I'd like to see it, but will pass on the crowds.

.JPG) |

| Picture: MS |

Then there's

Rembrandt: The Late Works, another obvious topic and a guaranteed blockbuster. The term 'blockbuster' used to be used to deride exhibitions, using a word from the entertainment business to rebuke museums for failing to provide anything more worthy. Now it's adopted proudly; the NG boasts that this will be a blockbuster, meaning that we should go to marvel at the huge crowds rather than the great pictures.

The earliest stirring of my interest in art was reading a book on Rembrandt in my junior school library. I remember marveling at The Blinding of Samson, which I've since seen several times in Frankfurt. And we had a print of The Man with a Golden Helmet, then thought to be by Rembrandt, in the school's corridor. I'd love to see this exhibition, but I'm not sure I'll be able to go at all. The busiest shows are literally un-seeable. I once traveled specially from Edinburgh, at a cost I could barely afford at the time, to see the El Greco exhibition at the National Gallery. I left after about ten minutes, because every picture was surrounded by a crowd three or four deep. You could just about catch a glimpse of the top of large pictures, then shuffle to the front and see a bit more a few minutes later. Now that I live in London, I have been able to buy season tickets and visit each exhibition several times to see a little bit on each visit. Now they've stopped offering season tickets, and there's no news on their replacement. They promise a 'friends' scheme, but no information has yet been provided and requests go unanswered (perhaps because they've got rid of their information department). Meanwhile timed entry slots begin to sell out.

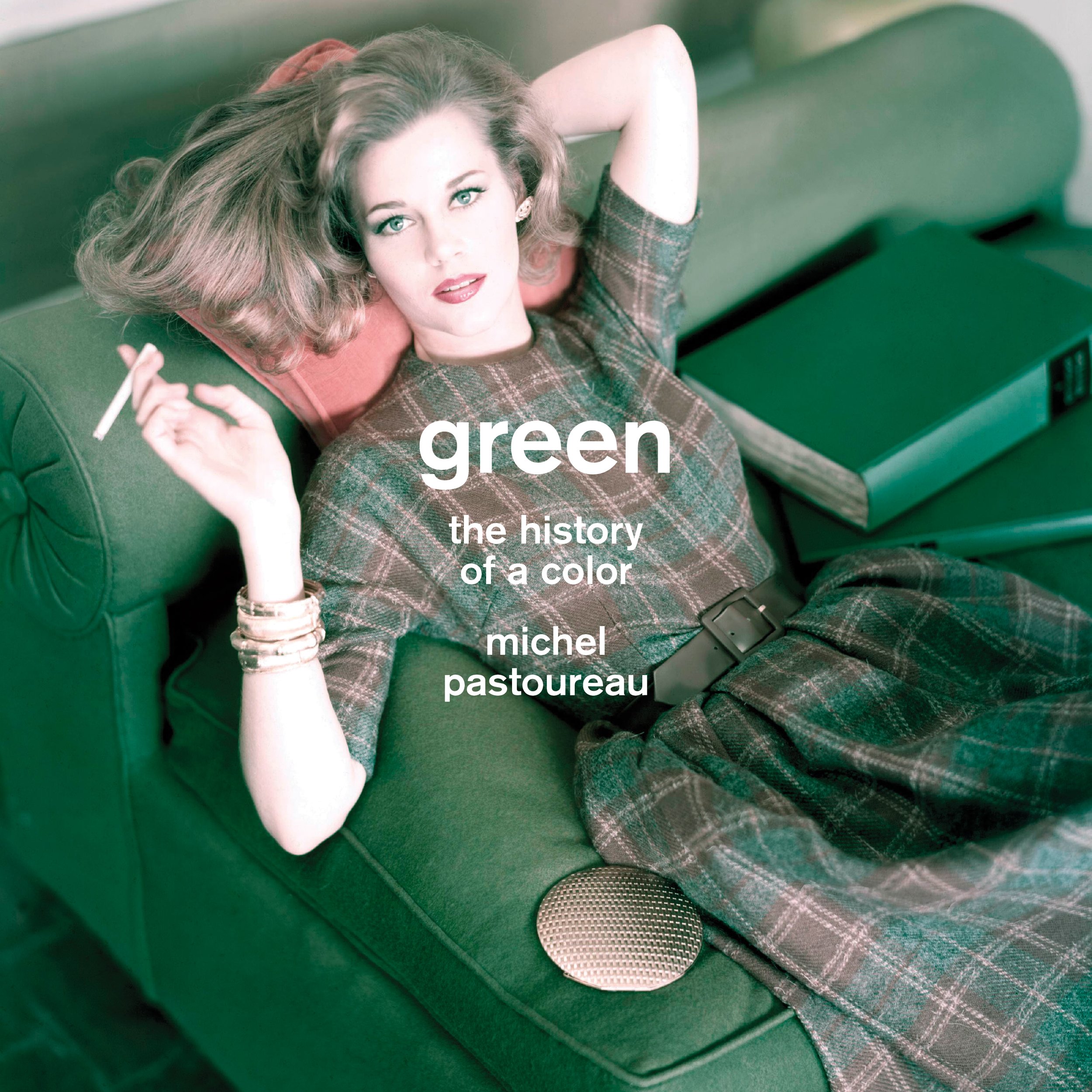

It would be arrogant to make any claims about my knowledge or appreciation of Rembrandt, but I can confidently say that few people can have studied him as intently as me. I have seen almost all of his pictures, making special trips to Minneapolis, Moscow and St Petersburg. I traveled to Holland simply to see Jan Six, which I made an appointment to see at the Six House in Amsterdam. I've read all that I can find about Rembrandt over a period of decades, and I've traveled to exhibitions of his work. The picture above is a shelfie of most of my Rembrandt books. But despite living in London, it seems likely that I will miss this major exhibition of his work. If you want more than a quick glimpse through a crowd, then I'm afraid this won't be for you. One of the pictures from Australia is one of the last Rembrandts that I haven't yet seen, but it's just not worth struggling to glimpse it through a crowd at the NG. Looking at art is supposed to be a pleasure, but going to these blockbusters is a painful chore.

Of course exhibitions shouldn't be only for people like me. But at the moment the cater generously to favoured professionals, with private out-of-hours tours in ideal conditions. You'd be surprised just how many of the people enthusing about the current crop of blockbusters will have seen them

privately. And they do all they can to entice people with limited interest, trying to boost footfall and engage new audiences. But once you have become interested and you seek greater engagement, you are taken for granted. The main thing they offered us was the season ticket, which has now been taken away. Can it really be their intention that people like me shouldn't visit this exhibition? Let's see if they ever respond to me on the season ticket replacement they have promised.

.JPG)