|

| Picture: Amazon |

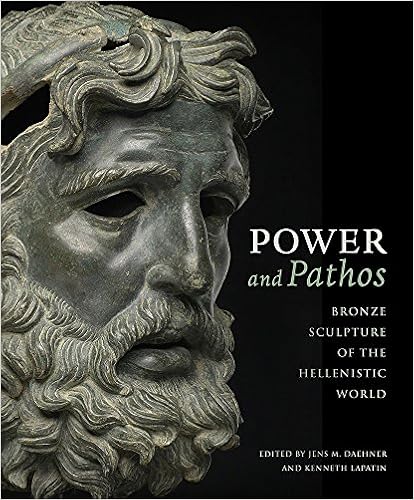

Jens M. Daenher & Kenneth Lapatin (eds) Power and Pathos: Bronze sculpture of the Hellenistic World J. Paul Getty Museum 2015 £42.91

I'm sorry I won't be able to see this show, currently at the Getty, but the wonderful catalogue is some consolation. This is what an exhibition catalogue should be: erudite essays, comprehensive entries for all exhibits, proper detail on condition and provenance, and great illustrations. I find these sculptures thrilling. Even if you know nothing of their context, they are immensely powerful works of art. But there is an extra frisson from sensing a connection with an ancient civilization far removed from ours, but feels so accessible through these universal masterpieces. If I have one criticism of the catalogue it's that this sense of wonder is dulled by a sometimes ponderous writing style. Oh, to see the exhibition in the flesh!

Most ancient bronzes have been melted down for scrap, but the precious survivals reveal them as a pinnacle of art history. Power and Pathos brings together some of the greatest. Some were discovered in the renaissance, and some may even have been handed down the generations from antiquity. A surprising number have been found quite recently, and the exhibition is an opportunity to assess them in the context of more familiar sculptures. But one of the greatest recent discoveries is missing.

|

| Picture: Cleveland Museum of Art |

The Apollo Sauroktonos only emerged in 2004 when it was bought by Cleveland Museum of Art. They say it may be a sole surviving bronze by Praxiteles, one of the greatest ancient sculptors. The catalogue gives short shrift to the idea it's by Praxiteles himself; there's just not enough evidence for that claim. But it's not actually in the exhibition, so we lose the chance to compare it with the canon of ancient bronzes. Sculptures have been brought from all over Europe for this show, but the Apollo Sauroktonos hasn't made it from Cleveland to Los Angeles.

It's a controversial sculpture. It was bought from a dealer that has broken the law in the US and Egypt, and its provenance is vague. Most suspicious of all is Cleveland's own secrecy; it refused to allow an academic access to its files on the sculpture. But technical evidence indicates that it was excavated a long time ago, and no specific claims have been made for restitution. That didn't stop the Greek government leaning on the Louvre and demanding its exclusion from an exhibition on Praxiteles. I don't know if specific threats were made over the Power and Pathos exhibition, but the chilling effect of Greece's threat to the Louvre may have been sufficient.

Looting of antiquities is an especially pernicious crime. It is so much more than property theft; it permanently deprives humanity of irrecoverable evidence of our history. Context is vitally important. But our rightful outrage at looting shouldn't stop us asking: does stigmatisation of antiquities without provenance stop looting? And what should we do with all the antiquities that lack provenance? Should they be hidden from view, never sold or loaned?

The debate has been distorted by moral and political grandstanding. Countries demanding restitution are not innocent victims heroically seeking to protect art and history. Italy wants to hoard everything found on its territory, but fails to protect and display what it has. Greece has made no claim for the Cleveland sculpture, yet it uses its power to stop its exhibition. Antiquities without provenance are being treated as 'dirty', as if the objects themselves have bad juju. Superstitious thinking doesn't stop looting. It stops scholarship.

That said, the Cleveland Museum of Art has behaved despicably. If the sculpture is clean, why are they so secretive? My request for information was simply ignored, and scholarly requests for access have been denied. That's not the behaviour of a serious scholarly institution with nothing to hide. Maybe they deserve to be called out and ostracised, their requests for loans boycotted. That seems like cutting off our nose to spite our face, but if peer institutions think the acquisition was unethical they should come out and say so. Instead everything is done in secret. Greece acts behind the scenes, threatening to deny loans if anyone borrows the Apollo. Other museums are too timid to criticise either the Greek government or the Cleveland curators. And the Cleveland Museum of Art keeps its lips sealed. Whatever your views on the antiquities trade, secrecy won't do anything to advance the debate.