|

| Picture: Amazon |

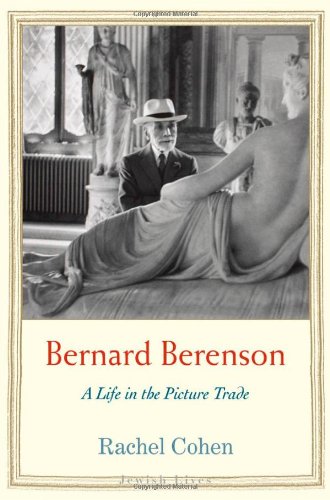

Rachel Cohen Bernard Berenson: A life in the picture trade Yale University Press 2013, £18.99

This short study is one of the best books written about Bernard Berenson, an art historian and one of the most fascinating figures in the intellectual life of the twentieth century. Rachel Cohen's beautifully written book brings balance and good sense to a subject that has has too often been distorted by hucksters and sensationalists. Mind you, his life was pretty sensational. Cohen describes him as "dignified and erudite but also capricious and heedlessly romantic; his arrogance was matched by his self-contempt" (p. 4). He was a great connoisseur, but his reputation is tainted by his secret association with notorious art dealer Joseph Duveen. He was a great reader and writer, and an art collector in his own right (unfortunately his collection is withheld from the world, cocooned in Harvard's study centre that has colonised his Villa I Tatti outside Florence). He was in many ways a nineteenth century figure stranded in the wrong time, a conservative - even a reactionary - who lived through Italy's fascist years, spending part of the war in hiding.

Cohen's study focuses on a few key themes: his Jewishness; his relationships with women; and his life in the picture trade. The book was written for Yale's Jewish Lives series, but Berenson's relationship to his Jewish heritage, whilst interesting, is not central to his life. Fortunately it's not central to this book either. His relationships with the women he was close to are much more interesting. Cohen discusses his sisters, his early patron Isabella Stewart Gardner, his wife Mary Costelloe, his librarian/companion Nicky Mariano, Edith Wharton, and J.P. Morgan's librarian and amanuensis Bella da Costa Greene. See also the cover photo, above! Berenson is renowned as a great conversationalist and correspondent who drew many of the greatest intellectuals of the twentieth century into his orbit (his correspondence with Hugh Trevor-Roper has recently been published). This book's focus on his more intimate relationships gives a different window on the life of his mind, and there are some wonderful quotations from his letters to Mary Costelloe, whom he later married. But most interesting is Cohen's take on Berenson's notorious connections to the picture trade.

Cohen appreciates the tension between Berenson's "passion for painting and his desire for wealth and security" (p. 272). Berenson's secret arrangement with Duveen is notorious, and he stands accused of puffing pictures that Duveen was trying to sell, and altering attributions to promote sales and earn his 25% profit share. Cohen rightly redresses the balance of blame, highlighting cases where he resisted pressure and recognising his internal conflict. She is nuanced on the question of Berenson's culpability, and rightly highlights the double standards between posterity's judgment of Duveen and of Berenson: "Toward both Duveen and Berenson, people were, and continue to be, indulgent, competitive, exculpatory, and dismissive - but, whereas Duveen is seen as charming, Berenson is both adulated and condemned" (p. 207).

Berenson had a major blind spot, which is that he dealt in images rather than painting. Cohen notes that he worked from photographs and "sometimes seemed almost unaware of what might be restoration" (p. 221). It's a flaw that we associate particularly with our own times, when internet images are so readily available. But many earlier art historians, curators and collectors were ignorant about pictures as physical objects. Berenson was sometimes critical of Duveen's outrageous restorations, but he was still complicit - and this is a far worse crime than signing a few optimistic attributions. His attributions transferred some wealth illicitly from American millionaires to himself and his partners - wrong, but relatively trifling in historical perspective. More damaging was the disservice to scholarship, but that's something that can be set right over time. It's his collaboration with Duveen's wholesale scrubbing of the works that passed through his hands that is most damning and most unforgivable because it has robbed us all of part of our artistic patrimony. Cohen's discussion of this is strong (pp. 221-223), but she could have made more of this shameful practice.

There are a few places where the art history is off-key. Rodolphe Kann did not own "ten glorious Rembrandts" (p. 167; some of his 'Rembrandts' are dreadful daubs, although he did own the great Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer), and his Castagno was uncertainly attributed when Duveen was negotiating its sale, though it is now generally accepted (interestingly its current owner, the National Gallery in Washington considers it a Castagno, but the author of its own catalogue, Miklos Boskovits, disagrees). But this short, erudite and articulate study redresses the balance of Berenson scholarship. I found the short length and narrow focus to be advantageous in addressing the most interesting controversies about this most interesting man, but our understanding could be enriched further by more research on the context of twentieth century connoisseurship and the art market.

Berenson's life is fascinating, but because he was such a great exemplar of a certain kind of intellectual, because he was clubbable and connected and articulate, and because he was flawed and human, his role has tended to be exaggerated. He was one of many experts for hire, and Duveen was only one of many flamboyant art dealers. It's not a criticism of this book, but the literature on twentieth century art dealing and connoisseurship is rather one-sided. Berenson is especially interesting for the conflict between high-minded ideas and grubby dealings that he personified. Other experts were the same, except that they lacked the high-minded ideals. There is much more to be said about connoisseurship and the twentieth century picture trade.

Marco Grasso has written a fine review for The New Criterion, with more background on Berenson.