Sculptures are hard to display. They need protection from curious hands, but they can't really be appreciated in vitrines. Sculptures are often seen as the poor relations of paintings, and don't get the same curatorial attention. That's why auction viewings are so worthwhile. The auctioneers do a much better job of showing their wares, and you can really appreciate the quality of this masterpiece. It's a logical acquisition for the Getty, which has developed a choice collection of sculptures. I hope they get it, because they display their collection so well.

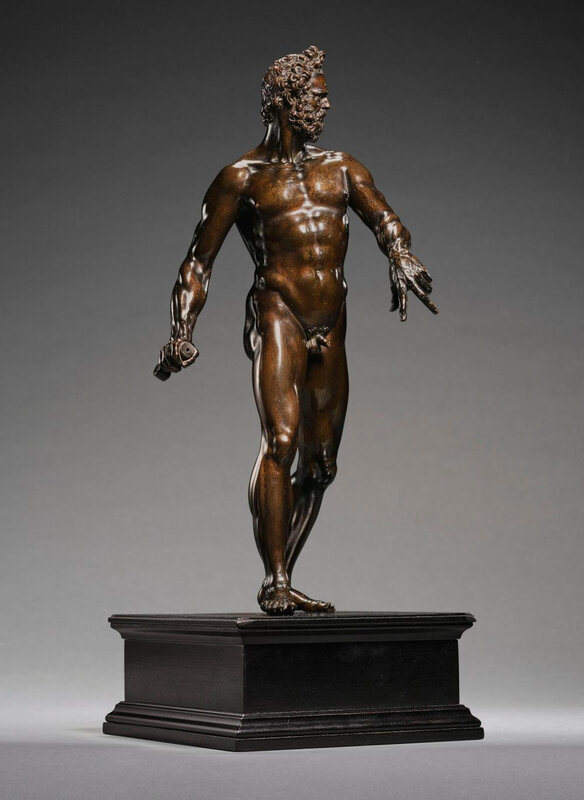

Christie's also leads with bronzes. There's a great group of Hercules overcoming Achelous by Tacca, an artist in Giambologna's studio. A gilt version of this is in the Wallace Collection, and comparing the two really emphasises the quality of the Christie's bronze. Estimate is 'on request', circa £5m. They also have a magnificent rediscovered masterpiece by Giradon, a large bronze of Louis XIV on Horseback (£7m-£10m).

The picture that grabbed my attention was this outstanding Portrait of a Man against a green background, plausibly attributed to Dürer. I don't know if it's by him or one of his close followers like Schongauer, but whoever it's by, it is a masterpiece. Condition is clearly compromised; the background looks horrible. It might have been overpainted and then cleaned. But the face itself is well-preserved and fabulous quality. This kind of picture is rare outside Germany and the estimate of £300k-£400k is modest, reflecting its small size and the diminished impact from damage to the background. The excellent catalogue entry gives more background on disputes over its attribution, which is welcome. Continuing with the northern Renaissance, Sotheby's also has a rare picture by one of my favourite artists, Hans Baldung. The Holy Family with Five Angels (£2.5m-£3.5m) is rather worn in the key parts, but other elements are still finely preserved. And they almost never appear for sale. Hugo van der Goes is another rare and prized master. The Adoration of the Magi at Sotheby's is only by a follower, but I like it a lot. And over 2m wide, it's unusually large and is good value at the estimate of £200k-£300k.

.jpg)

A tiny Jan Brueghel the elder, A Wide Village Street in summer with carts, villagers and gentlefolk (the title says it all) reminds me that he's a really great artist (£2.5m-£3.5m, Sotheby's). Not all his pictures rise to this level, and weaker ones appear at auction quite often. It's a beautiful and easily appreciated picture, but it's also a sophisticated image. Perspective is cleverly distorted; compare the trees on the left and the right. It's a trick used by Rubens, but on a tiny scale. When you see lots of pictures of this type you come to appreciate how hard it is to integrate those seemingly-random figures into a harmonious whole. It's a really great picture.

Sotheby's has a sleeper in reverse. This Ecce Homo is described as Venetian School, early sixteenth century, with an estimate of £30k-£50k. The catalogue note doesn't mention that it was previously offered in New York in 2009 with full attribution to Lorenzo Lotto, endorsed by Keith Christiansen of the Met, with estimate of $400k-$600k. It's still a fine, unusual picture. I wonder if it would have been better marketed without the initial Lotto attribution, encouraging the trade to bid it up as a sleeper.

There's a dearth of great drawings at this week's sales, but each auction house has a few spectacular things. There's an overwhelming early Fuseli at Christie's, The Faerie Queen appears to Prince Arthur (£150k-£250k, above). The most fascinating is a twenty-foot panorama of London just after the Napoleonic Wars, by Pierre Prévost (£200k-£300k at Sotheby's).

These are the big-money highlights, though not so big compared to contemporary art. I'll write a separate post tomorrow about the day sales and antiquities sales, where there are some really good pictures with really modest estimates.

.jpg)