|

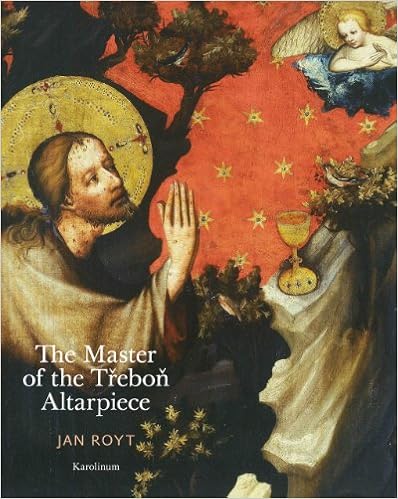

| Picture: The Art Fund |

The sellers have timed the offer well. The old master market is in the doldrums, but early English portraits are selling astonishingly well. Them seem merely clumsy to me, but their mix of 'merrie England' naivety and Tudor bling appeals to some of today's rich. I don't blame the sellers for timing the market. But Britain's public collections tend to mistime acquisitions perfectly, competing with the mega-rich for the most expensive pictures of the day and ignoring unfashionable bargains. The Art Fund has always known that this picture was in a British private collection. But they never seem to think strategically; did they try to buy it previously? And which unfashionable pictures are they trying to buy cheaply today?

And is this really a £16m picture? Portraits of Henry VIII from Holbein's workshop recently sold for £821k and £965k. They're not prime versions, but they're artistically better than the Armada Portrait, and equally iconic. I can accept that the likely prime version of the Armada Portrait is more valuable than studio replicas of Holbein's Henry VIII, but twenty times more seems a stretch. That money could buy a Titian or Rembrandt. For less than half the price (£7.3m) we could have had the fantastic Le Brun portrait bought by the Met, which is a great picture from a school poorly represented in UK collections. With the change we could have bought portraits by Scipione Pulzone, Ludovico Carraci and Girolamo da Carpi. Or for £14m we could have bought a great Poussin, an incomparably better picture. None of these are big names, and they're not especially fashionable. But we should be buying pictures based on quality and importance rather than choosing pictures that lend themselves most easily to publicity campaigns. Art collecting is being driven by public relations, which generally means pictures with some patriotic story behind them, because The Art Fund's PR department only has that one script.

If private donors think the Armada Portrait is good value, and really want to keep this picture in Britain, I won't stand in their way. I'll even agree that it would be a nice acquisition for the National Maritime Museum. But it's not just private donors. The Art Fund is largely subsidised by the taxpayer, in that its members receive free or reduced admission to publicly funded museums and exhibitions. That's a large part of why most people join, and that money funneled to The Art Fund comes straight out of the pockets of public museums. It's effectively a way of moving money from general expenditure to acquisition spending, but at immense bureaucratic cost. And The Art Fund seems especially unskilled at identifying the best things to buy.

There's another big subsidy in that £6m in tax will be remitted. I'm delighted by a £6m subsidy for the arts. But this is an arbitrary £6m subsidy, available only to specific works that are already in the UK. Effectively the government is paying full face value for a gift token that can be used only for one work of art, instead of just giving the money directly so that museums can choose the pictures they want.

The Art Fund has recently called for a review of the system of export licenses. I call for the whole rotten process to be abolished. If a foreign buyer is willing to pay £16m for this, let them have it. And let our museums compete to buy pictures from abroad, rather than having to go after the latest picture that The Art Funds wants to 'save'.