|

| Picture: Amazon |

Diane Fortunberry et al

Body of Art Phaidon 2015 £39.95

The term is meant as a put-down, but I love coffee table art books—big, sumptuously produced, designed for browsing. I appreciate the scholarly and serious as much as anyone, but coffee table books are an indulgence I'm not ashamed of. This new one from Phaidon is organised thematically, juxtaposing contemporary art and old masters with brief but incisive captions. They follow current fashion by imposing themes rather than following historical schools, which helps mix things up in interesting ways. It works for this kind of book, where narrative is less important, but the division is a bit hackneyed ('Beauty', 'Power', 'Identity'...). Chapters on 'The Abject Body' and 'The Body's Limits' work better.

My hesitation about the thematic approach is that it elevates art history above art, imposing categories that make sense to academics rather than ones that would have been recognised by artists. Old masters' peers were other artists. Some were certainly intellectuals, but I don't think their primary concern was making clever points about power or identity. Today that's probably less true, and artists and art historians do inhabit the same intellectual universe. But an approach that works for contemporary art becomes strained when it tries to incorporate the whole of art history.

The captions are interesting, and I found the discussion of (to me) unfamiliar contemporary works informative. Like a good guided tour, they pique my interest and tell me something new without trying to teach me everything. But I found the longer chapter headings and introductions weaker. For example, Jennifer Blessing's overall introduction celebrates contemporary "feminist and queer artists [who] refuse to accept ... facile dualistic conceptions of identity. Instead, gender and sexuality are understood as a continuous spectrum of possibilities, not as fixed binaries" (p.9). But the facile dualism is Blessing's; her contrast of ignorant past versus enlightened present isn't sustainable. Artists have played with identity, including gender identity, for aeons. Mannerists like Spranger and Bronzino were obsessed with shifting gender identity, and ancient sculptures of Aphrodite speak to the same concern. Cartesian dualism was an idea that arose quite late, and burned quite briefly.

A final concern—and this one is damning—is that the production is terrible. Some of the reproductions looks like they've been taken from old postcards. The most sumptuous masterpieces like Giorgione's Tempest and Sleeping Venus, and Titian's Venus of Urbino look like grainy 1970s reproductions. An expensive book like this should do much better. Phaidon used to be a market leader in art history, producing high-quality books with good illustrations at low prices. Now they seem to have conceded the high-ground to Yale University Press, which is utterly and unfortunately hegemonic. C'mon Phaidon, they need a proper competitor.

|

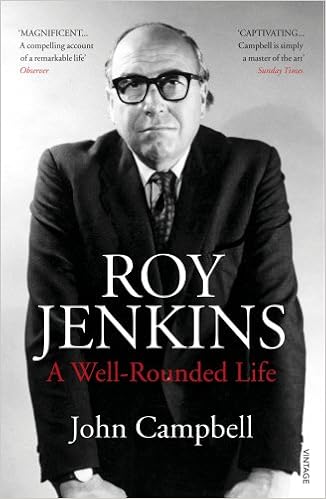

| Picture: Amazon |

A fine and meaty biography of one of the major figures in British political history. Campbell is a fan, and it's an authorised biography, but he's good enough to present a balanced picture. I am unsympathetic to Jenkins. He was born to Labour Party aristocracy and was a professional politician, but he had a taste for the high life. I like that. Champagne Socialism is surely the best kind of socialism. But his connoisseurship of politics didn't match his connoisseurship of wine. As I read the book I perceived a gap in the discussion of ideas, but actually I'm not sure Jenkins had many ideas, beyond a wishy-washy middle way consensualism.

Jenkins's great achievements were as Home Secretary and Chancellor of the Exchequer, but his tenure in both is over-rated. As Home Secretary he was the right man at the right time. His predecessors had been reactionary even by the undemanding standards of their time, and Jenkins was swimming with the current. His social liberalism was on the side of history; no great intellectual battle had to be won. And as Campbell sets out, in other respects he took a firm law-and-order line. Campbell's biography is weaker on economics, which is little matter as Jenkins's reputation as an economist was undeserved. He was less narrowly party-political than some of our more disastrous Chancellors, and avoided obvious disasters. But he largely gained credibility from a cyclical upswing.

The biography is well-written and engaging, but could do with tighter editing. We're told several times of his liking for Anthony Powell and Auberon Waugh, and of his preference for his Glasgow constituency over his Birmingham constituency, and details of the SDP split now seem rather arcane. But his treatment of Jenkins's private life is measured and well handled, and Campbell is a particularly astute reader of Jenkins's many books. I would be a little more generous; his biographies of Asquith and Gladstone are magnificent. I appreciate Jenkins as a writer more than as a politician.

I learned a lot from this enormously impressive book. If I call it a sociological study I know I'll lose most of you, but it's acute, well-written and compelling, full of quotable aphorisms: "What you accept in practice is more significant than what you reject in theory. The main sector of the left wing of the left rejects, in theory and in no particularly order: austerity, the capitalist system, American leadership and the oppression suffered by the Palestinians. It accepts, in practice, the single currency and ree trade. However, it would be an understatement to say that this pseudo-opposition felt no great compunction about marching behind pro-European leaders" (p. 82). He describes anti-racist slogans as "part of a multiculturalist logic that insists on the 'right to difference', which is a clinical symptom ... of a deep-rooted inegalitarian unconscious" (p. 141). But there's also data to back up his claims. It's an impressive, humane and nuanced account of a topic too often left to hysterical pundits.

Not a book that will appeal to everyone, so let me finish with something I can recommend without qualification:

The eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815 caused global temperatures to fall, weather patterns to change, harvests to fail. Art historians will know it as the cause of the dramatic sunsets that Turner and Friedrich painted.

I'm normally allergic to books that claim to identify something that 'changed the world', but this one is great. Wood explains the science wonderfully clearly: climatology, volcanology, and epidemiology. But he's equally strong on history and literature. I knew the story, in broad terms, but the detailed global explanation is fascinating. Well worth reading.