|

| Picture: Amazon |

This might be the most ambitious book ever written about art. Botton and Armstrong argue that art is valuable as a tool to address psychological needs rather something to be cherished for its own sake. They think through the consequences of that approach for the way museums are organised, the way art history is researched and taught, and the way art is traded. Then they offer their recommendations for remaking the world economy (really!). Unfortunately their reach exceeds their grasp. It's a bad argument that leads to worse policy.

The solace of art

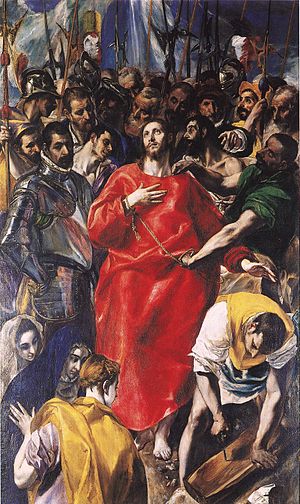

The claim that art meets psychological needs and provides solace is true but banal. The substance, and also the weakness, of the argument is in the specificity of its advice. B&A aren't really finding anything in art. They are bringing things

to art. The formula is to take a B&A homily, illustrate it with an old master and tell us that it's the old master's idea. For example, in a Poussin landscape: "the message from Poussin is that most worthwhile work, administrative positions, ambitious commercial enterprises or creative endeavours - irrespective of how they are seen from the outside - do not feel or look glamorous from the inside". None of that highfalutin stoicism here, thank you Professor Blunt! Poussin's intellectual contribution is reduced to the anticipatory plagiarism of an earlier

book by, er, Alain de Botton.

Take a closer look at the content of the idea and it becomes more insidious. For me art offers the chance to go beyond myself, to experience a sense of wonder, to sample the greatest creations of the human spirit from across cultures and times. For B&A, it's about reconciling us to limits, making us satisfied with what we've got rather than giving us a glimpse of something greater: "Art can do the opposite of glamourizing the unattainable; it can reawaken us to the genuine merit of life as we're forced to lead it". Life as we're forced to lead it has many merits, but for me the merit of art is that it transcends the petty limitations of daily life.

The book is packed with superficially attractive ideas that fall apart after even cursory consideration:

many outcomes are determined by how much [optimism] we bring to the task. This flies in the face of the elite view that talent is the primary requirement of the good life, but in many cases the difference between success and failure is determined by nothing more than our sense of what is possible and the energy we can muster to convince others of our due. We might be doomed not by a lack of skill, but by an absence of hope. Today's problems are rarely created by people taking too sunny a view of things; it is because the problems of the world are so continually brought to our attention that we need tools that can preserve our hopeful disposition.

This is careless, confused and wicked. It is careless in jumping between success and the good life, assuming that one is a continuation of the other. It is confused in asserting that it's an 'elite' view that talent is the primary requirement for the good life (who says that?). But it's also wicked. It's wicked to blame people's failure on the wrong state of mind, rather than acknowledging the role of ability, motivation and sheer luck. And it's wicked to imply that the ills of the world arise because we're too negative (I think exactly the opposite - and if I were to argue the case in a book, I'd at least do my readers the courtesy of providing some evidence for that thought). But is it even true that art can 'cure' a negative disposition? I generally find that it re-enforces my innate negativity; those of a sunny disposition may find the opposite.

Everyone is an idiot

B&A are weakest when they extend the trivial claim that art can provide solace to make the stronger claim that everyone else in the art world has failed to understand that, and they must therefore do everything differently. Two unsavoury implications are first that everyone else is a fool, and second that not only does art provide solace, but that it all that art can do - because once we've remade the world to suit B&A, there's not much room for anything else.

They open with the tired trope about curators who "can't remember what it was like to share the assumptions of an ordinary member of their society" before criticising wall text for talking about art rather than self-help maxims. Then they get really weird, suggesting that the Tate should cease building up a representative collection of schools of art, and instead "be guided by an analysis of the nation's collective psychological frailties". Instead of addressing gaps in the collection of cubists or surrealists, "they might take the view that they were strong on works that addressed loneliness but short on art that helped people form better relationships." The problem is that even if you accept that some works of art are especially suited to 'address loneliness' (do the subjects jump out of the frame to chat over a cup of tea?), it's not the only thing that art does. Those of us who want to learn more about art, to situate works in a context that would make sense to their creators, will simply be bamboozled by such a display. Individual works of creativity will be reduced to stage props to illustrate the nostrums of pop psychology.

Their criticism of academics is crushingly philistine, suggesting that we already know enough about art history and just need to communicate it better. They complain that university courses fail to ask 'what do these works mean to me?', and instruct that "scholars should study how to make the spirit of the works they admire more connected to the psychological frailties of their audiences. They should analyse how art could help with a broken heart, set the sorrows of the individual into perspective ..." - in other words, they should all become self-help gurus.

My favourite bit is when they tell art dealers what to do:

The task of the private gallery is a serious one: to connect purchasers with the art they need. The chief skill required for running a gallery should therefore be not salesmanship, but the ability to diagnose what is missing from the inner life of the client. The art dealer should strive to identify what kind of art a person needs to rebalance themselves and then meet that need as efficiently as possible.

The key activity of a dealer would be to conduct consultations sessions that would reveal the state of the client's soul. Before one can know what someone should buy, one has to know who they are, and more importantly, what areas of their psyches are vulnerable. The role of the art dealer would overlap with that of a therapist. The standard layout of a commercial gallery would evolve to include a therapy room, which one might need to pass through before getting to see any works for sale. Thus the dealer would operate as a matchmaker, bringing together an inner need of the client with a work best able to assuage it.

I'm amused by the image of Mayfair's art galleries with couches in the front room. "Freud or Lacan with your Gainsborough, sir?" The absurdity is funny, but it's also a sign of the unseriousness of their argument.

It seems cruel to continue, but let's finish by looking at their recommendations for remaking the global economy:

What we are aiming for is enlightened capitalism: a system within which businesses remain sufficiently attuned to economic reality to be profitable and to sustain and increase their own activities without needing outside support, but also stay focused on providing optimal goods and services. It means a business culture devoted to what is genuinely worthwhile and admirable as well as to the many disciplines required to flourish in a competitive marketplace.

They can aim at enlightened capitalism as much as they want, but if all they can do is espouse vacuous homilies about niceness they'll miss the mark.

To thine own self be true

An underlying problem is the thinness of the book's philosophy. They think that art can help us become better versions of ourselves. There's much talk about the 'self' and the 'authentic self'. This example can stand for many: "Growth occurs when we discover how to remain authentically ourselves in the presence of potentially threatening things". But what is this 'self'? Selfhood is a problem that philosophers (and theologians, psychologists and even artists) have wrestled with for millennia. B&A cut through this great exciting jungle of ideas with a banal 'commonsense' notion derived from self-help books. Is my 'authentic' self the one I wear to work or the one I take to the pub? Is it the kindly one self that pets kittens, or the hard-nosed self that reviews bad books? When we're unsure how to behave, how do we know which self is true? And should we be true to our 'own selves'?

Shakespeare was mocking Polonius when he had him tell Laertes "To thine own self be true". Laertes got everyone killed! We all learn to subordinate our own desires to social demands. What do we do when the desires of the 'authentic' self conflict with our responsibilities to others? The possibility isn't even considered here. They promise to "outline what might be happening in our inner depths when we say that works of art are good or bad", but they never do. The book is stuck at platitudes, hinting at bigger ideas about the self, invoking big concepts about love and nature, but never telling us anything beyond the commonplace

I think they're getting at a more superficial problem of reconciling conflicting desires where we have to discipline ourselves and suppress immediate wants to achieve longer term goals. It's not a problem of the 'authentic self' but a problem of motivation, the staple of the self-help industry. I don't share the snobbish disdain for motivational therapy; there are snake-oil merchants out there, but much of it is well-meaning and well-grounded. The problem is that Botton and Armstrong have ideas above their station. They repackage common nostrums with a few footnotes and call it philosophy, then add a few pictures and think they've reinvented art history. It's just Oprah Winfrey without the charm.

But what's this got to do with art anyway? When I visit a museum I don't want to be directed to contemplate my 'inner self' (a dark place indeed!). I like that art takes you beyond yourself, sometimes to enjoy uncomplicated beauty without thinking too deeply, or sometimes to contemplate bigger things and selves more interesting than mine. I don't go to an art gallery to be analysed and I'd resent bombardment with therapeutic platitudes. There are more things in heaven and earth, Alain, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

This book is not just bad; it's obviously bad. Its badness isn't disguised by dense prose and it doesn't hint at hidden depths. Criticising the quotations above is almost superfluous. To quote is to refute. Books this bad are generally best left alone; reviewing them feels like bullying. But it's called for here because of the unearned attention it had already garnered. The truly scary thing is that museums are so timid and so unconfident of their own authority that they pander to this hokum. The National Gallery has invited Alain de Botton to

speak, and the Art Gallery of Ontario is even organising an

exhibition around this fatuous nonsense. The best riposte I've seen was from Tiffany Jenkins on Twitter: "I would hate to visit an art gallery with Alain de Botton - take[s] all the joy and beauty out of it". Indeed.